file://localhost/Users/susanegunter/Downloads/Sue_North%20Park%201980-2.jpg

At our age, sometimes some small thing triggers an association and with it a flood of rippling memories that submerge us, blotting out our immediate present. For those of you who have forgotten their Proust (or perhaps have just shelved him for future perusal), that is what happened to the narrator, Marcel, in the “Overture” to Swann’s Way, the first of the seven volumes of Proust’s monumental Recherche du Temps Perdue, translated variously as “Remembrance of Things Past” or “In Search of Lost Time.” I prefer the latter title, as I think it more accurately expresses what Proust tried to do—and what all of us try to do as we grow old: capture what we have lost in a meaningful enough way that others might benefit from (or at least understand) our unique experiences.

I must confess here, on this page, that I have never finished said monumental text. At nineteen I started reading it in French, when I was spending the summer working at Ocean City, New Jersey. I was distracted from this interesting project by, of all things, a boyfriend who showed up. I was crazy about him and wasn’t sure whether he reciprocated my feelings, so I dropped my reading in favor of spending long afternoons with him in his tiny apartment just off the beach.

I didn’t pick up Proust again until my thirties. This time I tried to read it in English, so my reading went faster, but I stopped about 300 pages short of my goal. I even taught Swann’s Way in a seminar on Modernism (along with parts of Ulysses and all of James’s The Wings of the Dove—the students liked Proust best). In graduate school, while studying poetry with James Dickey, I wrote a couplet about Proust:

In Proust most single sentences of brevity are free

to underscore the weighty thought of madeleines and tea.

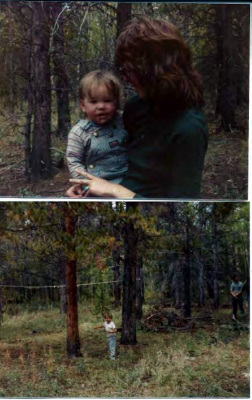

This brings me once again back to where I started—involuntary memory and how it places us squarely in the past. For Proust’s semi-fictional Marcel, it was the taste of a madeleine and lime flower tea that took him back to his childhood in Combray, with the magic lantern, the walks, his mother. For me it was the pictures above, which are of my two young sons during the summer of 1980, when we lived in field camp in the Mount Zirkel Wilderness area near the Colorado/Wyoming border. I took very few pictures that summer, but an old and dear friend, Craig Horlacher, sent Bill these photos a few days ago. I was instantly transported to what was one of the most interesting and challenging summers of my life. Bear with me—this probably will take weeks to tell, so hang on. . . .

So, field camp. In 1980, when Ben and Dan were small, we lived in the beautiful town of Poncha Springs, Colorado, population 250 plus (the plus being the friendly dogs who wandered its dirt streets). My geologist husband Bill was often away from home, leaving me alone with a three year old and a one year old. I had not even wanted children until I married Bill at age 28; I was surprised when I wanted them and even more surprised at how completely I loved them right away. Despite my continuing love for them, however, it was difficult to parent on my own so much of the time. I had become involved in the town—I was the town secretary and I belonged to a baby-sitting coop, an organic food-buying coop, and La Leche League—but still when Bill was gone for ten days at a time there were moments –hours—days—when I thought I would lose it. I used to take the boys to the high school track and put them in the middle of the field on the grass with their toys, while I ran round and round them as fast as I could. Or, when they were both napping, I would go outside and jump rope for hundreds of times. For some reason I did not go insane, but I did push Bill to a) find another career, b) send someone else from his office out prospecting, or c) move me closer to my extended family. I remember sitting in the corner of our log house rocking a crying child at night, watching for his truck headlights to come down the pass from Buena Vista. (This area was so remote that few cars ever passed through the town at night, in case you were wondering how I could recognize his lights.) And when he arrived, I usually turned over the boys to him and disappeared to spend the night in a motel in the nearest town, returning the next morning rested and happy.

So that was my life at that point. I vaguely recall that we fought fairly often, me because I was angry that we did not have shared parenting, Bill because he probably couldn’t figure out how to do anything about it. I think he loved his work, and frankly there aren’t many urban areas (with graduate schools and libraries) where he could have found employment. We laugh about all this now, but as I write about it I am there again and I can feel my own frustration.

At any rate, in the spring of 1980 he announced that he had a joint venture with a British company and a French company to fund a search in northern Colorado for a massive sulfide deposit. Well, fine—but it meant that he would be gone for several months, living five hours from our house. Great.

Instantly I hatched a couple of plans:

A) go back to Titusville, Pa., for the entire summer.

B) take the boys and go with Bill and all the others to field camp.

I had already made plans to go home for a couple of weeks in late May to visit, but when I got there I could see that my poor mother had deteriorated. She had been a polio victim as a child, and as she grew older she suffered various physical and mental ailments. My father was struggling to take care of her, and I realized that adding two little kids to the mix would not be helpful. My dear sister was there, but she too had young children, and her husband ran a big business out of their house. Unless I rented my own place in the town, plan A would not work.

But as I said in last week’s blog, according to Susann, always be ready to go with Plan B. I talked this over with my parents. My mother, who was a very bright woman and still in command of her mental faculties, said that Plan B was out.

“Susan, you cannot possibly take a three year old and one year old to live in a camp in the wilderness for months!”

Well, that did it. Unfortunately I am still that way: if someone tells me I can’t do something, I immediately figure out how to do it, whether it is good for me or not. And not only did I end up going, I ended up persuading my husband to hire me as one of the camp cooks for the summer. What a brilliant idea: I would earn a handsome $3.00 per hour, and my children could be by my side as I worked.

So off we went in early July. We were fifteen in all that epic summer: a middle-aged Aussie geologist escaped from the soulless bush for a six weeks’ sojourn in the green Rockies); four summer geology students (two male, two female—I had nagged Bill to hire women); a senior field technician with his wife, two year old, and eighty-three-year-old uncle Lyle; a young geologist and his pregnant wife; and the four of us, camp director Bill, three year old Benjamin, one year old Daniel, and me, a haggard thirty three year old. Two mixed breed dogs, two predatory cats, a herd of elk, and various uninvited rodents completed our singular entourage.

Together we spent the summer in one of the earth’s most beautiful spots. We were 37 miles from the crossroads of Cowdrey, population 45, and 42 miles from the town of Walden, population 1000. While much of the landscape in Jackson County, Colorado, is arid and open, dotted with cacti, sagebrush, juniper, and pinion, the Mt. Zirkel wilderness area is green and spectacular. Throughout the summer the field in our encampment was carpeted with tiny wild flowers, beautiful alpine orchid species in shades of violet, mauve, ad blue. This large open field was bordered by trees at its north end, where our tents were pitched, and sloped down to Beaver Creek at the south, dropping off over a steep brambly edge to the creek bed below. Parts of Beaver Creek were clear and rocky, though other sections widened into boggy mosquito-infested swamps.

An owl nested in a single tall dead tree in one such swamp a quarter-mile southwest of our camp; he circled our field on moonlit nights in search of tasty midnight snacks. At first these night sounds startled me: the owl’s clear hoot, the coyote’s chilling cries, the noises of large animals crashing through the high country timber. Morning sunrises were stunning. As the sun’s red light reflected on the snowy peaks to the west, it bathed our valley in a rosy glow. I loved the dawn quiet: privacy was at a premium here, with fifteen of us sharing common living areas. The three boys in the camp, of course, loved camp. They could play all day long—no structure, no media, nothing but insects, rocks, plants, and two happy dogs.

The camp was set up to expedite the mapping of significant geologic occurrences. The forest service had allowed us to build platforms on which to erect our large canvas tents. Each family group had a tent for sleeping, plus there was a large cook tent and another large tent that served as an office. Our site was next to an abandoned gravel pit filled with water; at first some of us bathed there, but as its water table lowered week by week it looked less and less inviting. There were two latrines set back from the camp in the woods. (My older son was potty trained when we went, but for weeks he refused to use these facilities, leaving me with two in diapers at a time when disposal diapers were scarce.)

Not only was there no electricity here, there was no water, so I arose at 5:30AM each day to take my water jugs down to Beaver Creek and haul them back up, next heating the propane stove to boil my water for coffee and for cooking chores. Sometimes when the boys napped in the afternoon, I would sneak back to the creek to wash my hair in the icy water, my head aching.

The hills around us were dotted with abandoned cabins. I used to think about the women who might have lived there. If I struggled for a short summer, what must it have been like for them when winter came, with no doctors, no stores, no neighbors. . . . . I have never fully been able to tell their stories. Next week I will finish this “camp cook” episode, leaving you to imagine what might happen next--debilitating illness, a psychotic breakdown, divorce—but you probably aren’t thinking “happily ever after!”

I must confess here, on this page, that I have never finished said monumental text. At nineteen I started reading it in French, when I was spending the summer working at Ocean City, New Jersey. I was distracted from this interesting project by, of all things, a boyfriend who showed up. I was crazy about him and wasn’t sure whether he reciprocated my feelings, so I dropped my reading in favor of spending long afternoons with him in his tiny apartment just off the beach.

I didn’t pick up Proust again until my thirties. This time I tried to read it in English, so my reading went faster, but I stopped about 300 pages short of my goal. I even taught Swann’s Way in a seminar on Modernism (along with parts of Ulysses and all of James’s The Wings of the Dove—the students liked Proust best). In graduate school, while studying poetry with James Dickey, I wrote a couplet about Proust:

In Proust most single sentences of brevity are free

to underscore the weighty thought of madeleines and tea.

This brings me once again back to where I started—involuntary memory and how it places us squarely in the past. For Proust’s semi-fictional Marcel, it was the taste of a madeleine and lime flower tea that took him back to his childhood in Combray, with the magic lantern, the walks, his mother. For me it was the pictures above, which are of my two young sons during the summer of 1980, when we lived in field camp in the Mount Zirkel Wilderness area near the Colorado/Wyoming border. I took very few pictures that summer, but an old and dear friend, Craig Horlacher, sent Bill these photos a few days ago. I was instantly transported to what was one of the most interesting and challenging summers of my life. Bear with me—this probably will take weeks to tell, so hang on. . . .

So, field camp. In 1980, when Ben and Dan were small, we lived in the beautiful town of Poncha Springs, Colorado, population 250 plus (the plus being the friendly dogs who wandered its dirt streets). My geologist husband Bill was often away from home, leaving me alone with a three year old and a one year old. I had not even wanted children until I married Bill at age 28; I was surprised when I wanted them and even more surprised at how completely I loved them right away. Despite my continuing love for them, however, it was difficult to parent on my own so much of the time. I had become involved in the town—I was the town secretary and I belonged to a baby-sitting coop, an organic food-buying coop, and La Leche League—but still when Bill was gone for ten days at a time there were moments –hours—days—when I thought I would lose it. I used to take the boys to the high school track and put them in the middle of the field on the grass with their toys, while I ran round and round them as fast as I could. Or, when they were both napping, I would go outside and jump rope for hundreds of times. For some reason I did not go insane, but I did push Bill to a) find another career, b) send someone else from his office out prospecting, or c) move me closer to my extended family. I remember sitting in the corner of our log house rocking a crying child at night, watching for his truck headlights to come down the pass from Buena Vista. (This area was so remote that few cars ever passed through the town at night, in case you were wondering how I could recognize his lights.) And when he arrived, I usually turned over the boys to him and disappeared to spend the night in a motel in the nearest town, returning the next morning rested and happy.

So that was my life at that point. I vaguely recall that we fought fairly often, me because I was angry that we did not have shared parenting, Bill because he probably couldn’t figure out how to do anything about it. I think he loved his work, and frankly there aren’t many urban areas (with graduate schools and libraries) where he could have found employment. We laugh about all this now, but as I write about it I am there again and I can feel my own frustration.

At any rate, in the spring of 1980 he announced that he had a joint venture with a British company and a French company to fund a search in northern Colorado for a massive sulfide deposit. Well, fine—but it meant that he would be gone for several months, living five hours from our house. Great.

Instantly I hatched a couple of plans:

A) go back to Titusville, Pa., for the entire summer.

B) take the boys and go with Bill and all the others to field camp.

I had already made plans to go home for a couple of weeks in late May to visit, but when I got there I could see that my poor mother had deteriorated. She had been a polio victim as a child, and as she grew older she suffered various physical and mental ailments. My father was struggling to take care of her, and I realized that adding two little kids to the mix would not be helpful. My dear sister was there, but she too had young children, and her husband ran a big business out of their house. Unless I rented my own place in the town, plan A would not work.

But as I said in last week’s blog, according to Susann, always be ready to go with Plan B. I talked this over with my parents. My mother, who was a very bright woman and still in command of her mental faculties, said that Plan B was out.

“Susan, you cannot possibly take a three year old and one year old to live in a camp in the wilderness for months!”

Well, that did it. Unfortunately I am still that way: if someone tells me I can’t do something, I immediately figure out how to do it, whether it is good for me or not. And not only did I end up going, I ended up persuading my husband to hire me as one of the camp cooks for the summer. What a brilliant idea: I would earn a handsome $3.00 per hour, and my children could be by my side as I worked.

So off we went in early July. We were fifteen in all that epic summer: a middle-aged Aussie geologist escaped from the soulless bush for a six weeks’ sojourn in the green Rockies); four summer geology students (two male, two female—I had nagged Bill to hire women); a senior field technician with his wife, two year old, and eighty-three-year-old uncle Lyle; a young geologist and his pregnant wife; and the four of us, camp director Bill, three year old Benjamin, one year old Daniel, and me, a haggard thirty three year old. Two mixed breed dogs, two predatory cats, a herd of elk, and various uninvited rodents completed our singular entourage.

Together we spent the summer in one of the earth’s most beautiful spots. We were 37 miles from the crossroads of Cowdrey, population 45, and 42 miles from the town of Walden, population 1000. While much of the landscape in Jackson County, Colorado, is arid and open, dotted with cacti, sagebrush, juniper, and pinion, the Mt. Zirkel wilderness area is green and spectacular. Throughout the summer the field in our encampment was carpeted with tiny wild flowers, beautiful alpine orchid species in shades of violet, mauve, ad blue. This large open field was bordered by trees at its north end, where our tents were pitched, and sloped down to Beaver Creek at the south, dropping off over a steep brambly edge to the creek bed below. Parts of Beaver Creek were clear and rocky, though other sections widened into boggy mosquito-infested swamps.

An owl nested in a single tall dead tree in one such swamp a quarter-mile southwest of our camp; he circled our field on moonlit nights in search of tasty midnight snacks. At first these night sounds startled me: the owl’s clear hoot, the coyote’s chilling cries, the noises of large animals crashing through the high country timber. Morning sunrises were stunning. As the sun’s red light reflected on the snowy peaks to the west, it bathed our valley in a rosy glow. I loved the dawn quiet: privacy was at a premium here, with fifteen of us sharing common living areas. The three boys in the camp, of course, loved camp. They could play all day long—no structure, no media, nothing but insects, rocks, plants, and two happy dogs.

The camp was set up to expedite the mapping of significant geologic occurrences. The forest service had allowed us to build platforms on which to erect our large canvas tents. Each family group had a tent for sleeping, plus there was a large cook tent and another large tent that served as an office. Our site was next to an abandoned gravel pit filled with water; at first some of us bathed there, but as its water table lowered week by week it looked less and less inviting. There were two latrines set back from the camp in the woods. (My older son was potty trained when we went, but for weeks he refused to use these facilities, leaving me with two in diapers at a time when disposal diapers were scarce.)

Not only was there no electricity here, there was no water, so I arose at 5:30AM each day to take my water jugs down to Beaver Creek and haul them back up, next heating the propane stove to boil my water for coffee and for cooking chores. Sometimes when the boys napped in the afternoon, I would sneak back to the creek to wash my hair in the icy water, my head aching.

The hills around us were dotted with abandoned cabins. I used to think about the women who might have lived there. If I struggled for a short summer, what must it have been like for them when winter came, with no doctors, no stores, no neighbors. . . . . I have never fully been able to tell their stories. Next week I will finish this “camp cook” episode, leaving you to imagine what might happen next--debilitating illness, a psychotic breakdown, divorce—but you probably aren’t thinking “happily ever after!”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed