- For today’s craft lesson, I have chosen to focus on Sylvia Plath’s five bee poems, poems she intended to conclude her final book of poetry, Ariel. We too frequently get caught up in the facts (and myths) of her benighted life, sometimes to the neglect of focusing on her mastery at crafting language. After reading these poems, I will give you a reading on etymology, apply it to her poems, and then give you a prompt for writing, letting you choose words with suggestive origins that might help you deepen the meanings of your own writings.

Plath wrote her bee sequence, five poems, in one sleepless week in the fall of 1962, just four months before her death in February 1963. In her own arrangement of the Ariel poems in her black spring binder, these five poems were at the end of the book. In her own words, she meant for the collection to begin with the word “Love” (“Love set you going like a fat watch”, the first line in “Morning Song”) and end with the word “spring” (“The bees are flying. They taste the spring,” the last line in “Wintering”), thus framing the manuscript with words of hope. When Ted Hughes, the husband who had deserted her for Assia Wevill, edited Ariel after his former wife’s death, he did not follow her arrangement. Rather, he chose to end the volume with “Edge” (The woman is perfected / Her dead / Body wears the smile of accomplishment”) and “Words” (a white skull, / Eaten by weedy greens”), a far different conclusion.

Plath’s own choice for Ariel’s final poems, the bee poems, trace another trajectory, a move from fear to one of regeneration, to the possibility of a spring rebirth. In “The Bee Meeting,” the first person narrator goes to a bee meeting for inspiration and information. In the second, “The Arrival of the Bee Box,” she gets a box of bees. "Stings" the bees are transferred to the hive, and the queen flies off to mate; in "The Swarm" the colony has doubled and now divides; and in "Wintering" the bees hone in, clustering for heat, venturing out only on warm days to remove their dead, and thus, they live out the cold.

Plath’s father Otto, who died when she was just eight, had been an entomologist, writing a book titled Bumblebees and Their Ways. She herself took up in beekeeping in Devon in June of 1962, when she was living in Devon with her two small children. She wrote in her journal, “I should study botany, birds, and trees; get little booklets and learn them, walk out in the world. Open my eyes.”

In fact, it was the women in Devon who taught Plath the art of keeping bees. Although her neighbor, Charlie Pollard, would instruct her some and even give her one of his cast-off hives, it was her midwife, Winifred Davies, she would rely upon for sensible advice that summer into fall, and the "blue-coated woman" from British Guiana whom she met at that first bee meeting. "Today, guess what, we’ve become beekeeepers!" she wrote home to her mother that June (Letters, 457) "Now bees land on my flowers," she told Elizabeth Compton Sigmund, a Devon friend, about the flowers she had painted on her hive.[10] Late that October, she would go to London to read and be interviewed for the BBC by Peter Orr. Although choosing not to read any of her poems about them, she spoke of the bees and the enormous value of her midwife's instruction. "I'm fascinated by this, this mastery of the practical . . ." she told him. "I must say, I feel as a poet one lives a bit on air . . ."[11]

In the first poem, “The Bee Meeting,” we see the speaker’s hysterical self-absorption, her paranoia about the villagers who lead her to the hives. She is alienated from a human community, and her relationship with nature is confused. While the villagers seemingly intend to protect and include her, the black veil they give her becomes a death mask. She projects the fear she imagines that bees feel when they are smoked out of their homes. By the time she comes to “Wintering,” however, her fears have subsided. The poem contains a “cradle of Spanish walnut,” both an image of her own fecundity and one of rebirth. She enters a dark space in the first half of the poem, going into the cellar as a metaphor for entering her own subconscious. But she feeds the bees through the winter, looking forward to their renewal in spring.

She struggled with the final lines for “Wintering.” Draft one gives us “What will they taste of, the Christmas roses? / Snow water? Corpses?” Then she added "A Sweet spring?" but crossed it out. "Spring?"-left intact. "Impossible spring?"--crossed out. "What sort of spring?"-crossed out. "O God, let them taste of spring" crossed out. By the third draft, things had moved into typescript, and the final line into frozen, fully tragic images: Snow water? Corpses? A glass wing? But even here, though "snow water" and "corpses" remain, the glass wing has several lines through it, and handwritten then, at wild angles, are all her spinning options, her stop-start movement toward the right final lines: "A gold bee, flying?"-crossed out. "Resurrected"--crossed out. "Bee-song?"--crossed out. "Or a bee flying"--crossed out. Everything, in short, crossed out until, in a jubilant cursive--"The bees are flying. They taste the spring."

Here are Plath’s five bee poems. Read each poem carefully, noting key words and phrases. Enjoy them—they are lovely, an incredible achievement for a poet so young.

“The Bee Meeting”

https://www.americanpoems.com/poets/sylviaplath/the-bee-meeting/ - “The Arrival of the Bee Box”

- https://genius.com/Sylvia-plath-the-arrival-of-the-bee-box-annotated

-

“Stings”

www.best-poems.net/sylvia_plath/stings.html

“The Swarm”

https://genius.com/Sylvia-plath-the-swarm-annotated

“Wintering”

www.best-poems.net/sylvia_plath/wintering.html

For our craft lesson today, I will ask you to consider etymology as you make word choices. Here is a link to an excerpt from Natasha Sajé’s Windows and Doors; A Poet Reads Literary Theory. I highly recommend it as a way of deepening your understanding of how poems are put together, with the goal of enriching your own reading and revising.

natasha_etymology.docx

Plath herself was a master wordsmith. I looked at a few of her word choices in terms of their etymology. The word “bee” itself, has origins in the modern German biene < Germanic *bini; all going back to root bi-, perhaps = Aryan bhi- ‘to fear,’ in the sense of ‘quivering,’ or its development ‘buzzing, humming.’ Plath may have known that “bee” has connotations of fear. Even had she not known this, a reading of the repeated “bees” as “fear” or fearful can deepen the poems. The word “black” repeats throughout the sequence. One root of that word is the Proto-Germanic blakaz, meaning “burned.” Adding this meaning to the already somber connotations of “black” allows us to consider the burning emotions the poet must have felt as she composed the poems. Another word “rector” appears twice in the first poem, its Proto IndoEuropean root “reg,” meaning “to move in a straight line,” this meaning intensifying the pressures she feels to conform to this group of village beekeepers.

For your prompt today, choose a few words that are significant to you, either for a poem you have not written yet or from a poem you have considered revising. Take some time and look up the etymological origins of the words. There are a number of online resources. One I have found useful is:

https://www.etymonline.com

Finally, our recipe for today is my sister-in-law Laura Lee Gunter’s fudge pie. For years she made these pies and sold them to restaurants in Nashville. Well, needless to say those days are gone—at least the days of going to a restaurant and being served a slice of this delicious treat. I personally find chocolate comforting now.

fudge_pie.docx

I am indebted to Natalie Richter for ideas in this essay. For further analysis of Plath’s development as a writer and acceptance of her life as see in the bee poems, see her:

http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/131/sylvia-plaths-bee-sequence-a-microcosm-of-poetic-development fiction, nonfiction, and poetry

A journal you might consider for submitting one of your poems is Invisible City, the on-line journal published by the M.F.A. program at San Francisco State. Contact them at Invisible City

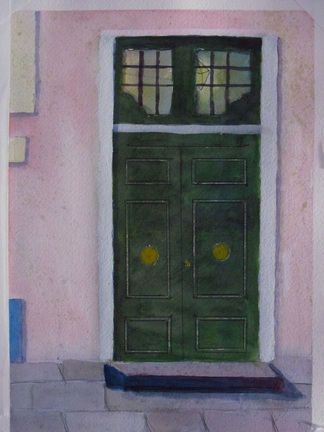

- Finally, I am including one of my watercolors. It was recently featured on the Best American Poetry blog, chosen by David Lehman.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed